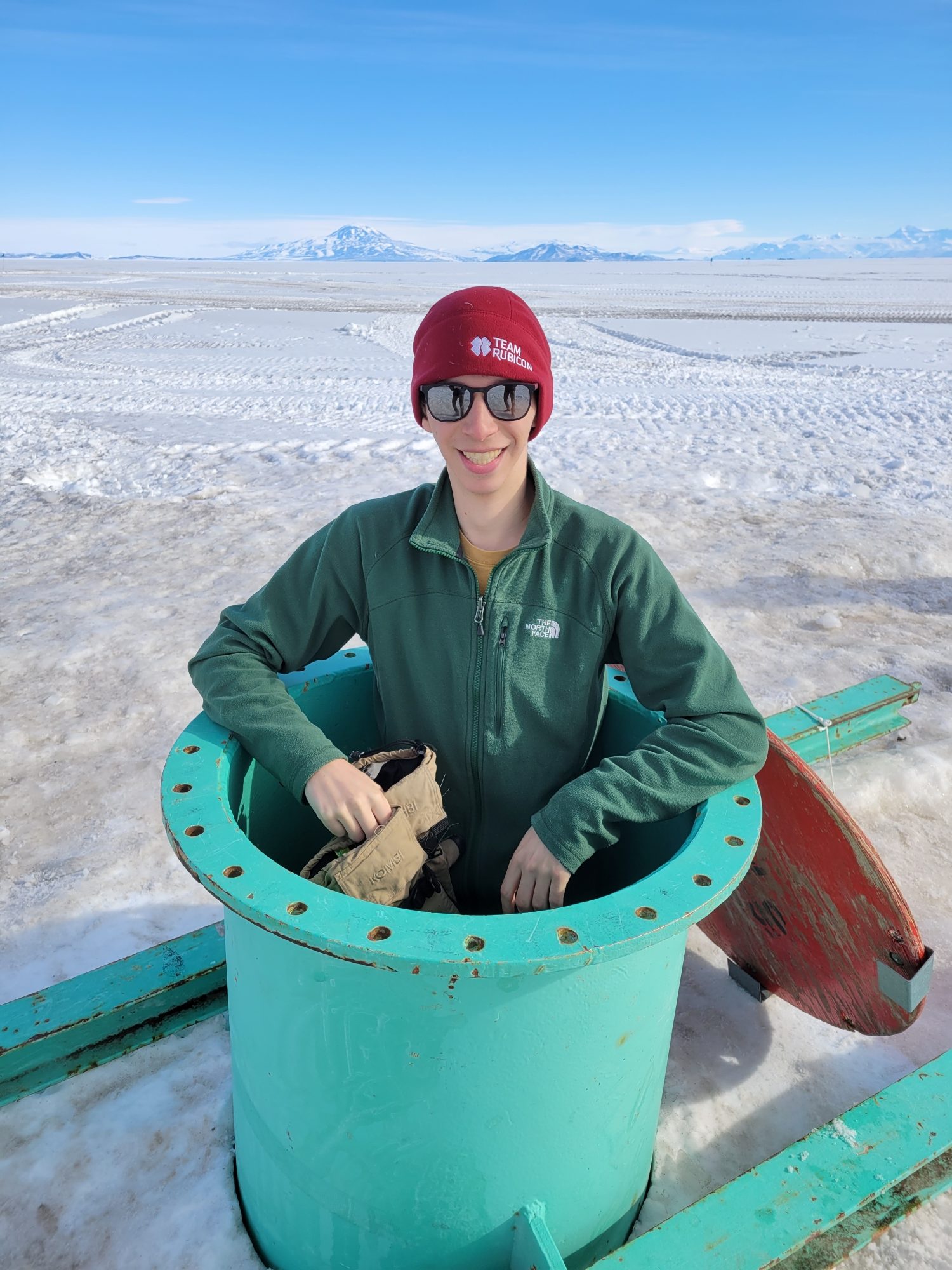

A CFRN in Antarctica

In his first year as a flight nurse, Jonah Pregulman, MSN, RN, CFRN, CEN, TCRN, CTRN, CPEN, NRP, delivered care on long-distance Lear jet flights transporting ill and injured patients throughout the USA, Canada and tropical islands for MedWay Air Ambulance and also flew on King Airs and PC-12s for CalSTAR transporting patients 30 days old and up. He later worked on a variety of international fixed wing aircraft. Before and in between flight nursing roles, he worked in EDs and as a travel nurse, and earned five BCEN credentials including the CFRN.

From October 2022 – February 2023, Jonah fulfilled his most unique nursing role yet … working on assignment as the flight nurse in Antarctica.

Tell us about the program and how you found out about it.

I actually found it on Indeed when I was searching for flight nurse jobs. The U.S. Antarctic Program is the U.S. scientific program in Antarctica. It’s run by the National Science Foundation, which then contracts out to various organizations to provide the support group. This is anyone from the cooks and janitors and people who run the housing, to the plumbers and electricians, to the healthcare providers, which typically included a nurse admin and 4-6 doctors and advance practice providers who staffed the medical clinic.

Antarctica, which is literally covered with a 2-kilometer-thick sheet of ice, is so big and so far away, it’s hard to wrap your head around it. The continent is the size of the USA and Mexico put together! The U.S. Antarctic Program operates three bases there. McMurdo Station, where I was, is the biggest with up to 1,200 people in the artic summer. There’s also the South Pole Station, which can have up to approximately 100 people. Palmer Station, which is very isolated from the other two stations, doesn’t have an airstrip big enough for a LC-130, so you have to take a boat from South America to get there.

My role was to be the primary flight care provider for patients needing to be transported within or off Antarctica. In my year, I was the only civilian flight nurse and, as far as I knew, the only CFRN. The U.S. Air Force (USAF) is a program partner and sends a flight team consisting of a flight surgeon, a flight nurse and a flight tech—part of whose job was to help with logistics, patient care and to be my liaison with the USAF flight crews.

My inflight team was a rotating group of USAF officers and medics with varying backgrounds. All were very knowledgeable about aircraft and flight physiology. They were also experts in the aircraft being utilized, USAF LC-130s and C-17s. The nurse was a commissioned officer and the medics were enlisted airmen, but they didn’t always fly with me. The need to maintain flight medical crew at the station meant we did not always send the entire crew. So, depending on the severity of the patient, typically one or the other would go with me with the other staying behind in reserve.

Most of the time my work was in the clinic at McMurdo Station helping to take care of their usual patients—respiratory infections, cuts, bruises, scrapes, bumps, and general medical issues. But, every now and again we would have a patient that needed to be flown out. At that point, my realm was packing the equipment, requesting the medications I needed, and thinking about any kind of logistics in terms of patient care. The Air Force provided the aircraft and took care of flight logistics including international border crossings. However it was an international effort and sometimes the New Zealand or even Italian Airforce planes were utilized.

What’s involved with an Antarctic aeromedical transport?

It was completely different in pretty much every respect to my civilian experience. In the States, it would be, we have 30 minutes, let’s get the patient to the airport.

It was completely different in pretty much every respect to my civilian experience. In the States, it would be, we have 30 minutes, let’s get the patient to the airport.

All of the patients were flown from Antarctica to Christchurch, New Zealand, which was the closest tertiary hospital. It’s approximately a 9.5 hour flight on a C-130, and that’s the longest flight that I’ve ever done as a flight nurse, at least continuously. A Lear jet can go 3.5 hours without needing fuel, and a King Air even less, at two hours.

An Antarctic transport requires a great deal of thought and coordination because there are so many steps and people involved. You need to coordinate the aircraft with the Air Force. The aircraft needs to be fueled, which requires a specific group of people to be called up. You need to open the runway, so that’s another 5-10 people to open the tower and open the aircraft maintenance. You need to select your medical flight crew, deciding who is rested and has the required skills.

Is the patient ready and stable enough to fly? Do we need to pack their stuff because they might not be coming back? Are they a scientist working on a research project or one of the critical support crew … and what are the implications of their being away? Do we have their passport? Can we get pre-immigration clearance to skip immigration once we get to the airport. We have to wake up the fire department to drive the ambulance to the airstrip and have crash rescue standing by. Is the weather okay? Sometimes we couldn’t fly because the weather was that bad or the visibility was horrible. Is the aircraft in working order? Antarctica is really hard on aircraft.

It was a 40-minute trip to the airstrip in the ambulance. Once you get there you have to load the patient. None of these planes are set up as permanent medical planes. So, you need to load the stretcher, tie it down, and get all your equipment, emergency items and medications loaded in. The C-130 doesn’t have on-board oxygen, so you have to bring tanks and strap them in after calculating how much you might need.

Just loading your patient in the aircraft is a formidable challenge. If it’s -10° F with the wind chill, you’ve got to think about whether the IV is going to freeze, is the patient going to freeze, and is the pump going to work at -10 degrees? Your fingers freeze. So being able to provide patient care with gloves on … meaning warm gloves not patient care gloves … was something I’d never run into. Just taking off your gloves to do something with the patient would mean your hands would go numb. So, you put your gloves back on and warm them up while you are simultaneously loading everything in.

Were there any notable patient transports you can tell us about?

Sometimes the only place available is a passenger type plane and it doesn’t have the space for a big medical crew and equipment, so creativity is required to determine if its safe for the patient, med crew and other passengers.

A difficult case was an undifferentiated migraine/headache who had all of the symptoms of a possible brain bleed, but there is no CT scan, just X-ray and ultrasound. In the more traditional hospital, it would be easy. We’d send them to CT, and would be able to rule out any bleeding in the brain, however this is not possible.

So, pre-flight, I consulted with the USAF officer specializing in flight medicine and the sending provider on the “what ifs.” In flight there is no communication with outside help, so I had a code sheet with all the drugs already calculated plus some up-to-date clinical articles describing certain situations and medications I might need to use. And also, I made sure I had all those little connectors and bits and bobs. Because once you take off, you are not coming back.

A more common issue encountered was with abdominal pain where we weren’t sure whether it was colitis, constipation, appendicitis, or any of the other things that can happen in the belly. While we had basic labs and x-ray films, without a CT scan to rule things out, it’s pretty hard to differentiate. So, for those who continued to have pain, we had to fly them out.

What did you take away from being part of the program?

It really helped with my diagnostic stills and with thinking ahead of everything I might need or want to know. If you don’t have a CT scan, is this patient sick or not sick? And I’d never had flights that were nine hours before. So, I had to carefully calculate how much oxygen and medication I really needed, and think through all the things that could happen … the “what ifs.” What if this patient codes—the worst possible situation—and I have to sedate them and intubate them? Do I have enough sedation for nine hours? And that was just our flight time. Start to finish, it could be a 12-hour trip, from leaving the clinic, waiting for the aircraft to get there, taking off, getting there, taxiing, bad weather, and many other factors.

In the civilian world, I usually have access to a satellite phone or another CFRN. Here, there was no satellite phone. It was often just me.

Anything you’d like to add?

Being responsible for patients knowing you are the flight nurse was a bit of a daunting task. Sometimes imposter syndrome is real. But knowing I was a CFRN … and that I really do know what I’m doing has been great. It is also a big green flag to employers and people in the know … because having the CFRN known is an accomplished certification to have.

I feel like having your CFRN proves you can provide safer and more effective patient care when it counts. It is a badge that you have the knowledge to safely care for patients in an environment that most nurses or providers would never think of practicing in.